The most recent city Transportation Commission meeting is the first time I've been interrupted with boos from Alameda residents while I was speaking from the dais.

When I came home and mentioned that to my spouse, she pointed out that she's regularly booed in her own line of work.

In an ideal world, we would take our turns speaking and listening. No one would be booing or be booed. And we'd all set good examples for one another. But in 2025, writing a blog post that's a generalized call for civility feels almost a bit too sanctimonious and maybe even beside the point. So, in this case I'll try to learn from my wife (she's an 8th-grade teacher) and simply carry on with the job at hand.

Instead of blogging about the agenda item that elicited those strong reactions, this post is nominally about other agenda item that was in front of the Transportation Commission that evening: Caltrans's I-580 Truck Access Study.

I-580's unique advantages for hill dwellers

There is only one stretch of Interstate freeway in all of California that bans semi trucks: the portion of Interstate 580 running through the hills of Oakland and San Leandro.

It's not due to physical reasons. I-580 is built to engineering standards that can handle semi trucks. This is demonstrated whenever there are major crashes on I-880 and the CHP temporarily permits semi trucks to instead travel on I-580. If the powers-that-be decided today, semi trucks could instantly drive on both freeways, with truck drivers and their dispatchers deciding which route makes the most sense for each trip.

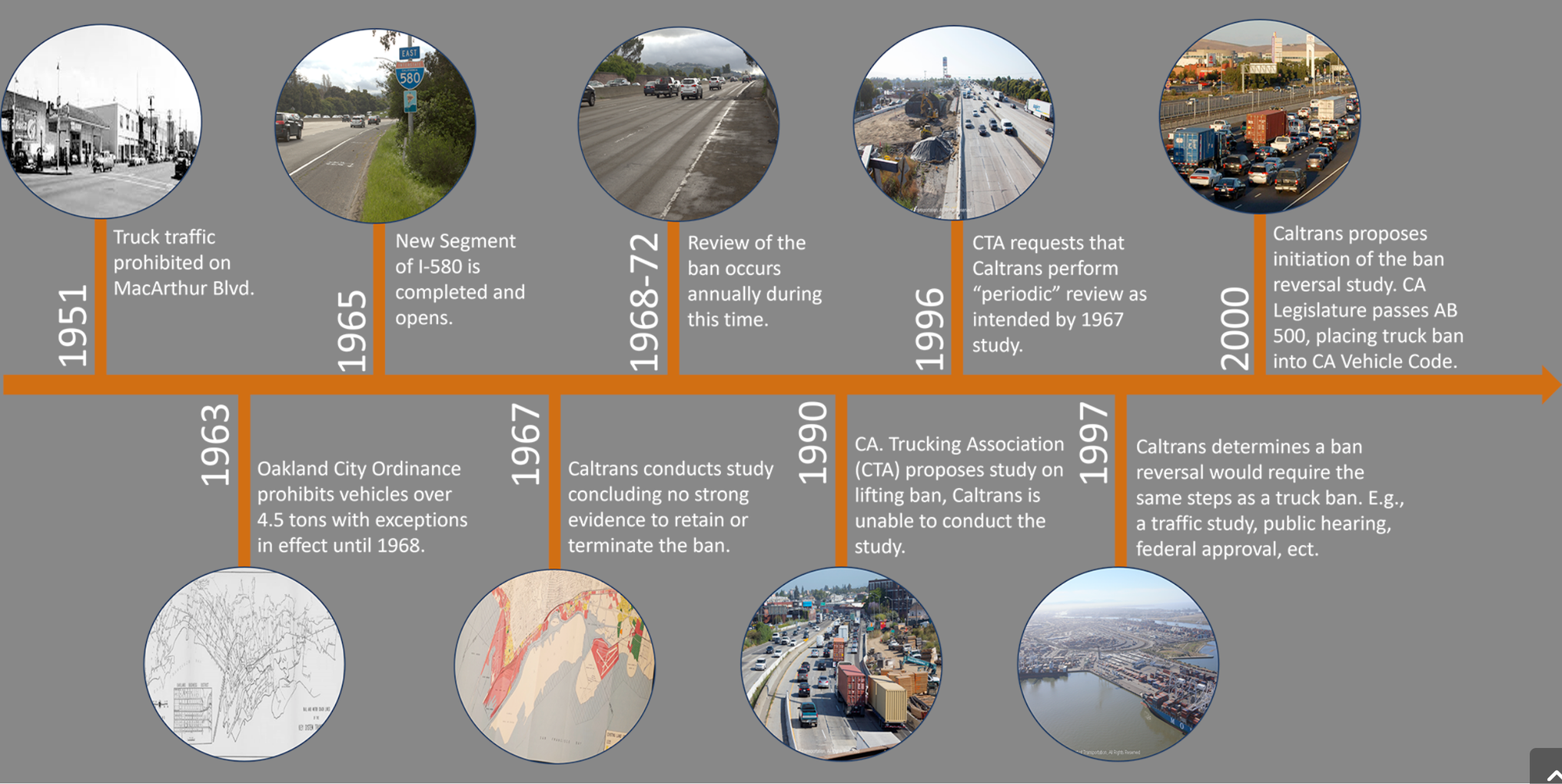

This ban is instead due instead to reasons that predate many of us. The truck ban was carried over from the boulevard that traversed the Oakland Hills before I-580 was built. And it's been re-affirmed — and strategically ignored — by various decision-making bodies over many decades:

To summarize: The reason why semi trucks aren't allowed on 580 is because semi trucks aren't allowed on 580. It's a fully circular argument that's convenient for some of the people who live in the hills alongside 580 — and to others, it's been an argument that's perhaps easier to ignore.

Kids from the flat lands questioning the status quo

But as young people are often known to do, a middle-school class started asking questions about that status quo. As reported by KQED in 2021:

“It just hurts to know that our community is slowly dying because of this air pollution,” says student Jasmine Orejudos.

Orejudos and her classmates live in East Oakland, a region traversed by the Interstate 880 highway. The freeway is heavily used by large trucks, bringing goods from the Port of Oakland to the rest of California and the country. The majority of those trucks are powered by diesel.

Most of students at Life Academy are Latino, and studies show communities where Black and Latino people live are overburdened with pollution. Students have been making connections between the dirty air they breathe and some of the poor health they experience.

“Me and my granny both have asthma and sometimes we can’t even go outside to enjoy ourselves because of the diesel-burning trucks,” said student Rodney Moten.

While many factors can cause and exacerbate asthma, diesel exhaust is one of them. Residents of East and West Oakland have the highest asthma hospitalization rates in Alameda County, which health experts say is worsened by breathing diesel pollution wafting down from the highway and over from the nearby Port of Oakland.

As the class studied air quality issues, they came across a state law that seemed odd to them. For 70 years, large trucks have been banned on a stretch of the Interstate 580 freeway that runs along the base of the East Bay Hills in Oakland and San Leandro. As a result, large trucks nearly exclusively drive through — and pollute — neighborhoods in Oakland’s flatlands.

This realization got students like Belinda Castro wondering: “Why are large polluting trucks banned on I-580, the highway that runs through the Oakland hills, but not the 880, the highway that runs through my neighborhood?”

The students aren’t the only ones questioning this decades-old ban. Alameda County Supervisor Nate Miley, who supported the ban in 1999 when he was on the Oakland City Council, said he’s changed his thinking.

“Knowing what I know now, I would make a different decision to try to phase it out,” Miley said. “We need to take steps to phase that ban out.”

[...]

Students are pushing for one more thing, something community advocates have been demanding for decades: a study of the ban’s health effects. And there has been some movement on that front. Bay Area air district officials said in an email to KQED they are committed to studying health impacts of the 580 truck ban, “probably in the 2022-2023 time frame.”

Is process progress?

The study requested by that class of middle-school students in 2021 (and estimated for the "2022-2023 time frame") has just now been started by Caltrans (in 2025).

KQED recently returned to this topic and spoke to the now-former teacher of those middle-school students (my own emphasis added in bold):

Former Oakland teacher Patrick Messac called into the meeting. In 2021, his sixth-grade class helped reignite the debate over the ban.

“My students were in sixth grade when district staff said that there was going to be a study, and now they are in high school,” he said during public comment. “I just really want to encourage the district to move forward with haste and intention.”

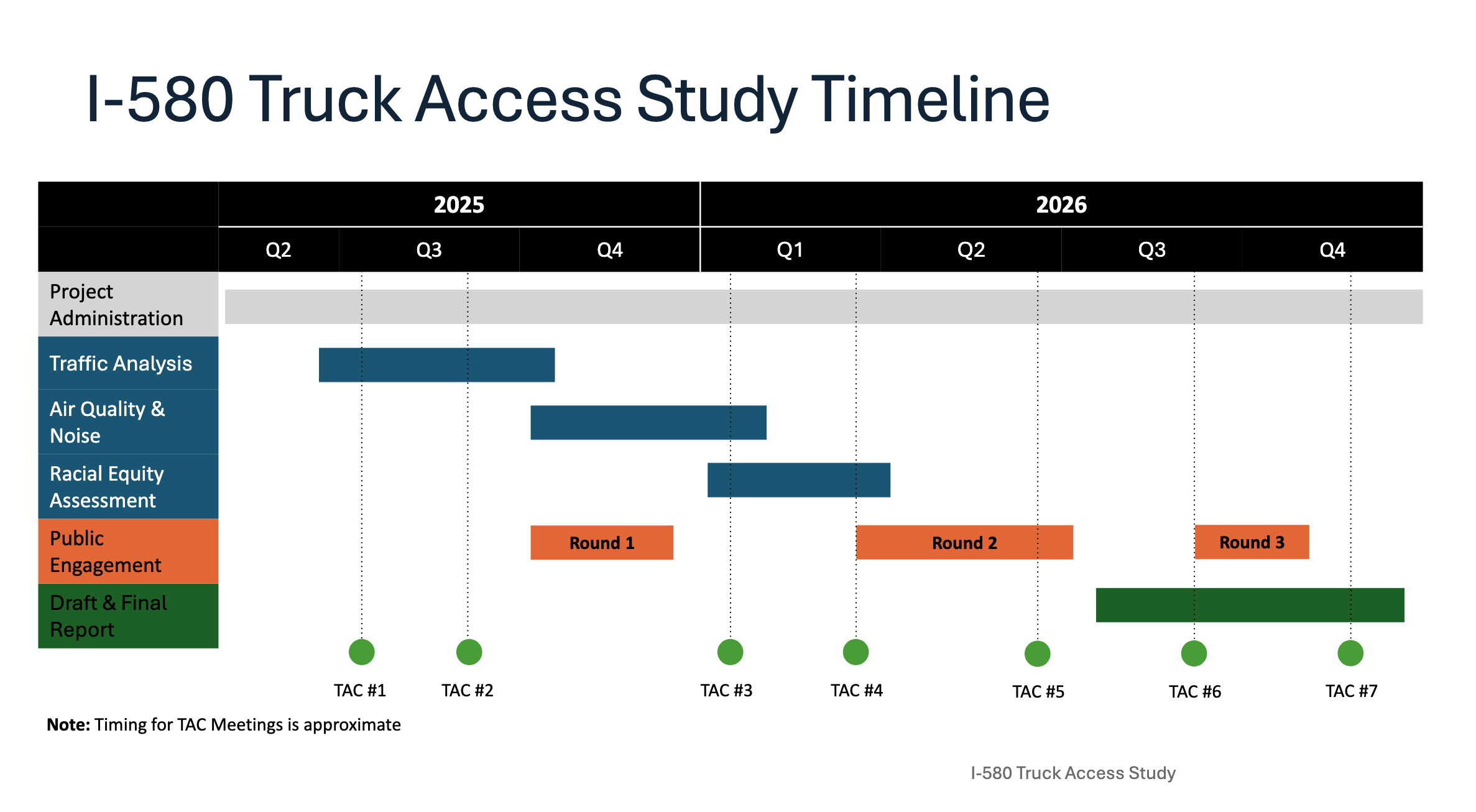

Here's the timeline for the next year of work that Caltrans District 4 staff presented to the Alameda city Transportation Commission:

Does all this multi-step process represent progress?

It's progress in that before those middle-schoolers started asking questions (and earning media coverage), the status quo was settled: semi-strucks and their traffic and pollution belong only in the flat lands of the inner East Bay. Now that status quo is open to inspection. Is that an equitable status quo?

However, it's not necessarily progress in that the end product of this process is simply a report. Any actual change to the I-580 truck ban will have to be enacted through state-level legislation.

It's also not necessarily progress in that all of this process is costing so much time and money. (I'm not able to find the budget for the I-580 Truck Access Study right now. Perhaps we can ballpark it in the high six figures or low seven figures?) That's money and staff time and public-engagement effort that's not available for other regional transportation needs.

Processes and consultants and Gantt charts may seem like the natural order of the public sector. But in this case they’re also decisions — decisions that protect the people who benefit from the status quo or are simply scared of change. By choosing a long, multi-phase study with a still uncertain outcome, we are collectively choosing to ensure that change comes, if it comes at all, only after a slow march of memos and technical appendices and hearings — very much the opposite of "haste and intention," to use the words of the students' teacher.

Are such drawn-out processes fair? Are they, when placed in the larger contexts and needs and priorities of a region or a city, equitable? To ask questions like that may get you booed.

Process can't replace politics

Leaving aside questions of fairness — and the apparently triggering word of equity — perhaps we can instead simply agree that some decisions about street and freeway networks are ultimately, to a certain extent, political.

Not entirely political. There are genuine facts on the ground that specialists can measure and model (although a traffic engineer's model is itself an interpretive exercise making some of its own normative assumptions).

Still, there's just enough of a political aspect to these decisions of priorities that we'd all benefit from being clear-eyed about what's going on.

KQED recently quoted the mayor of San Leandro "caution[ing] the group not to have blinders on while considering the study":

“I don’t want to see us … try to attribute all variations due to air quality on the highway when there are many other factors that go into that,” he said, noting that employment and diet are also linked to health.

He also said there is more infrastructure for large trucks, such as warehouses, around I-880 in San Leandro.

In contrast with the Oakland students' questions, that mayor's comments sure sound mealy mouthed. Sure sounds like he doesn't want to say anything that would potentially offend the hill-side residents of San Leandro. Compare that equivocation to the bluntness of county supervisor Nate Miley quoted earlier in this blog post:

"Knowing what I know now, I would make a different decision to try to phase it out. [...] We need to take steps to phase that ban out."

Although it's still worth noting how for all his directness, the county supervisor still proposes a phased process.

For better or worse, a process like Caltrans's I-580 Truck Ban Study is required to prepare the ground for what will ultimately (but not entirely) be a political decision by the Bay Area's legislative leaders in Sacramento.

It's unfortunate that so much time and money will be required to open even this possibility. I, for one, think it's worth being frank about these types of processes, since:

- In the immediate term, bluntness like Supervisor Miley's signals to staff (and their consultants) that they have sufficient cover to move ahead with the process until the next political decision point.

- Few changes to ground transportation networks are truly zero-sum tradeoffs. (The distribution of semi trucks on 880 and 580 is practically zero-sum, but other city and regional transportation projects are rarely that black-or-white.) For many projects, having a reasonable (but not unbounded) amount of public debate can identify improvements that engineers and planners would otherwise miss and that lead to a better overall outcome for all.

- In the longer term, speaking openly about the reality of transportation politics helps to engage a broader public. Not just a subset who feel they must "defend" their neighborhoods against change, but also a wider and more representative sample of residents and workers and business-owners and everyone else who cares about overall efficiency, effectiveness, and fairness.

We’ll always need a certain amount of process. And as with any political matter, leaders choose for themselves when and how to spend their finite capital on contentious decisions and the resulting tradeoffs (since there's never only one public priority at a time). We can genuinely aim for outcomes that are broadly beneficial and minimize negative side effects. But even then, it’s worth regularly checking whether a process is illuminating choices and preparing the ground for change — or whether it’s being used to avoid choices and delay change indefinitely. Booing feels a tell for the latter. Still, like chants of six seven! six seven!, it will pass.