When someone is concerned about speeding drivers and decides to make a request for traffic calming on SeeClickFix, to email city staff, or to give a public comment at the Transportation Commission or City Council, odds are that they will ask for the following:

- We need speed bumps!

- And we need stop signs!

And to the majority of these requests, the city's civil engineers and transportation planners will reply politely but curtly with a no.

Their reasoning against speed "bumps" for many street situations is straightforward to explain (and I'll do so briefly below) — but their reasoning against stop signs is harder to explain. The latter involves language that sounds ambiguous to laypeople and involves one of the most sacred of American traffic-engineering professional practices.

Bumps vs. hump vs. lump (a.k.a. cushion)

- Speed bumps have a sudden slope, leading to an aggressive jolt. They're only appropriate for parking lots and locations where drivers need to be slowed almost to a stop (less than ~5 mph).

- Speed humps, in contrast, have a more gradual slope. The goal of their physical design is to slow traffic to under ~20 mph. The new Neighborhood Greenway treatments along Pacific Ave include some speed humps. City staff are currently working on a policy with standard criteria for other streets and locations around the city where speed humps may be eligible to be installed. There's no money budgeted to make this happen, but the first step is having a policy in place to help qualify and prioritize potential locations being requested by SeeClickFix, emails, etc.

- Alameda also has speed lumps, which have been on Bayview Drive since at least 2007, but today's staff prefer to refer to those as speed cushions. While these are gradual like humps, the lumps/cushions don't span the entire street width — instead, emergency vehicles may roll through cut-out slots.

So instead of requesting a speed bump to slow drivers on a city street, try requesting a speed hump.

Speed control vs. traffic control

Now let's talk about stop signs. Here's a little skit to demonstrate:

Layperson: Drivers are speeding on Main Street. We must have a stop sign!

Traffic Engineer: Thank you for being engaged in our community! No, we cannot install a stop sign on Main Street.

Layperson: No?! Why?

Traffic Engineer: A stop sign is not a speed-control device.

Layperson: Huh? It literally makes people slow down!

Traffic Engineer: The M.U.T.C.D. says that "STOP signs should not be used for speed control."

Layperson: Huh? Then what is it?

Traffic Engineer: A stop sign is a traffic-control device.

Layperson: Speed and traffic are the same thing. So, please install a stop sign on Main Street now!

Turn-taking

The above misunderstanding can be clarified if you think of a stop sign as encouraging turn-taking by the users of an intersection.

When the engineer is saying a stop sign (or a traffic signal) is a traffic-control device, they're saying that it structures an order on how all the users of an intersection wait their turn, observe others, and decide when to proceed through the intersection. The fact that drivers have to slow down in advance of a stop sign is necessary, but that's almost just a side effect of its intended purpose: to control users' turns once they reach the intersection.

It then follows that different types of traffic controls may be relevant to intersections based on the volume of users coming from each direction:

- A large amount of traffic in all directions warrants a signalized intersection with lights.

- A medium amount of traffic in all directions warrants a four-way stop.

- A medium amount of traffic in one direction, with a light amount of cross traffic, warrants a two-way stop.

These examples are for hypothetical intersections of two streets at right angles, but you can imagine many more scenarios in which there are different volumes in various directions, with drivers, pedestrians, and cyclists all needing appropriate traffic controls to structure their turn-taking.

Warrants

With our layperson's new understanding about turn-taking, let's try that skit again:

Layperson: Hello again.

Traffic Engineer: I love our engaged community. How can I help you?

Layperson: We need a four-way stop at the corner of Main Street and Elm Street to control traffic. Pronto!

Traffic Engineer: No.

Layperson: Why? I said the magic words of "traffic control" this time.

Traffic Engineer: We'd have to conduct an engineering study, but I'd still reckon that the intersection of Main Street and Elm Street does not meet the warrants for an all-way stop control.

Layperson: Huh? This is like that Seinfeld episode but instead of "no soup for you!" it's "no stop sign for you!"

Traffic Engineer: I love our engaged community. Have a good day.

The key word to focus on in this skit is the word "warrant."

It's not a generic word meaning to justify in the abstract. For a traffic engineer, a warrant is a formal approval process. While it's not issued by a judge (as in a law-enforcement warrant), a traffic-engineering warrant is still only met under carefully guarded criteria.

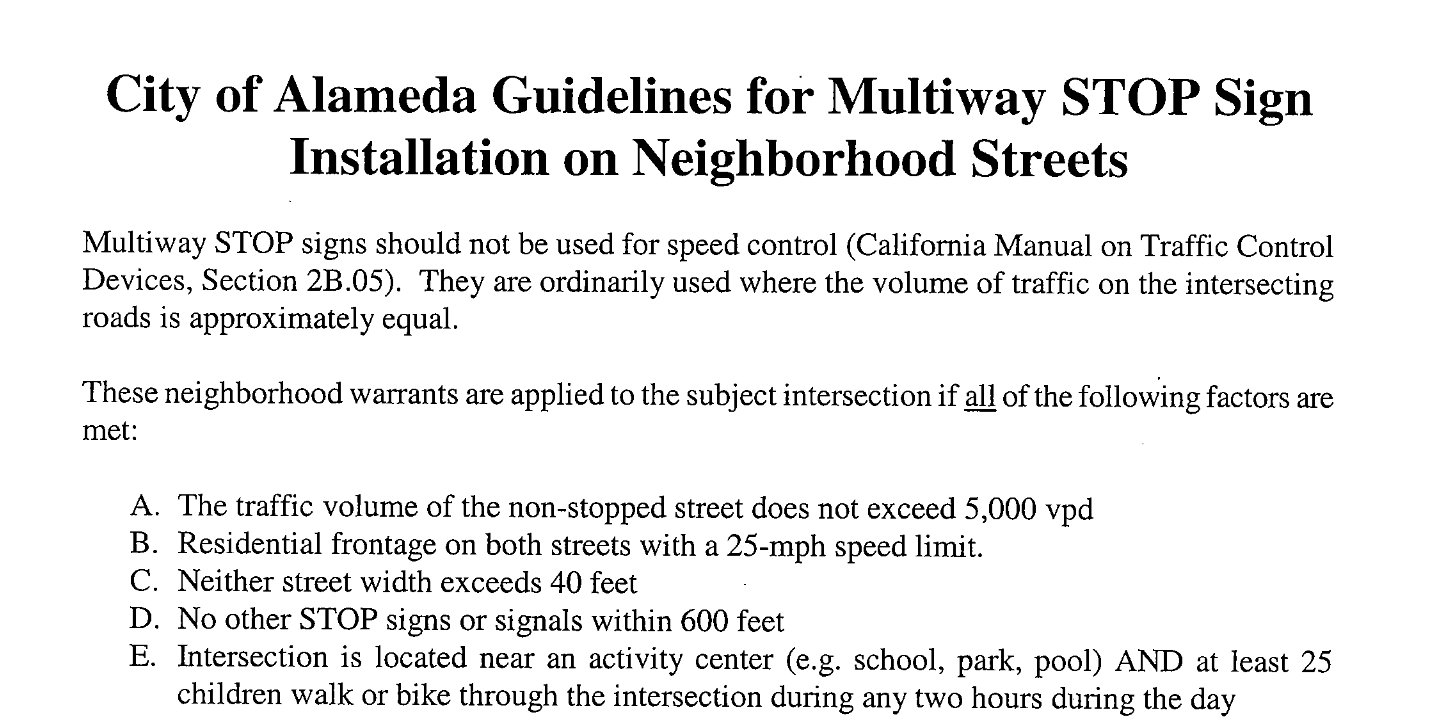

For a four-way stop to be installed in Alameda, these are the warrant criteria that must be met:

If the intersection does not meet all those criteria, then it doesn't meet the necessary warrants. For intersections that pass that initial gauntlet, they must meet additional criteria:

The city's traffic engineers retain more flexibility in applying these criteria, although a general skepticism shows through. This profession does not want to install stop signs... unless they can be fully justified and documented through the warrant process.

"Pay no attention to the [engineers] behind the [stop signs]"

Why the conservative, almost defensive attitude toward stop signs? The M.U.T.C.D. (postwar American traffic engineers' Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways) offers this:

Or put more floridly: American traffic engineers are like the Wizard of Oz in the first half of the book/movie/musical.

Each traffic control device represents the will of the great Wizard. A red octagon-shaped sign shall mean "halt before proceeding" on the order of the great Wizard of Oz! The green circular light shall mean "continue" on the order of the great Wizard of Oz! And so on...

But what if the wizard overplays his hand and asks too much of his subjects? What if the wizard has munchkins install stop signs anywhere and everywhere residents desire?

That wizard may eventually find his authority ignored and may be shouting into his microphone Pay attention to the stop sign, not to the engineer behind the curtain! while the drivers roll through a growing number of the intersections marked so carefully with red octagons.

So in an effort to retain authority, the wizards of the roads have used their Talmudic-like M.U.T.C.D. to define different categories of controls — traffic controls vs. speed controls — and to then dictate a series of warrants that must be carefully documented and met. To approach the Great Oz to request a stop sign is not undertaken lightly!

Traffic controls vs. roadway designs

The point of this blog post is primarily to explain the disciplinary practices of American — and Alamedan — traffic engineers so that laypeople can figure out how to more productively share their concerns and feedback with the city's professionals.

Let me end with two suggestions:

- Instead of advancing to asking for a particular solution (like a stop sign or a speed bump — or flashing crosswalk signage), tell city staff and Transportation Commission members and City Council members about what's happening. Be specific about what's going on. Share your frustrating, and share your worries. Make a big stink, collect a petition, take pictures, collect stats, and get the attention that dangerous spot deserves. But let staff bring specific solutions to the conversation. Alameda has forward-thinking planners, engineers, and consultants — they can use current best-practices to craft options to slow drivers, enforce better roadway behavior, and walking and biking less stressful for all ages and abilities.

- Let's redesign roads to physically guide everyone toward safe speeds and well-paced turn-taking. Traffic controls are the wizard's controls: signage, paint, and lights. All of which require the careful modulation of professional discernment and societal obedience to succeed in reality. They may be necessary but are rarely sufficient. The geometric design of a street, on the other hand, uses hard physical reality to shape the behavior of drivers, pedestrians, and cyclists. For instance, while an all-way stop only works when all users obey the Wizard, a neighborhood traffic circle filling the center of an intersection uses more elemental forces to guide drivers to slow as they navigate their vehicle around it. Just as black-and-white suddenly turns to color in the MGM movie, the adoption by Alameda and other cities of the candy-colored NACTO design guides represents a vibe shift for our streets. Instead of just imagining stop signs and speed bumps and lumps, let's imagine chicanes and gateways and pinchpoints... [oh my]... and speed tables with pinchpoints that serve as raised crosswalks... [oh my]... and center-line hardening with waist-high vertical delineator posts. (A few of these features are now deployed as "quick-builds" on Alameda's Pacific Ave. Neighborhood Greenway. And the one-block "woonerf" at the western end of W. Atlantic Ave. shows what can be fully realized when a street is built to be shared.) Our future can be much more colorful than simply stop-sign red.