Some streamers and a photo marked the intersection at which, 10 years earlier, a young Alameda resident, who was riding his bike at the time, was killed by the driver of an SUV:

This was two years ago, when I noticed that temporary memorial. In the meantime, I've read some of the news coverage from 2011 — and I've watched, curious to see how the City of Alameda might (or might not) improve this stretch of roadway when it would be next due for maintenance.

That maintenance has begun, and so I'd like to try to consider this intersection an an example of how the American traffic/civil engineering professions and how our broader society deals with traffic safety.

The three E's

Ask professionals how to decrease the number of injuries and deaths on American roadways and you may hear them reply with the shorthand of "the three E's."

- Education encourages safe behavior by teaching drivers, cyclists, and pedestrians;

- enforcement of traffic laws to discourage unsafe behavior;

- and engineering designs infrastructure using concrete, paint, and other physical materials to be used safely by all of these travelers.

The "three E's" originated a century ago. Their purpose has changed over the years, as has the notion of traffic safety itself. In the early 20th century, the "three E's" articulated the new field of traffic engineering and its focus on removing children, adult pedestrians, cyclists, pushcarts... anything other than motorized vehicles from roadways... in the name of traffic safety. In the latter half of the 20th century, the "three E's" have been used to address all the negative fallout from the legacy of that earlier generation of traffic engineers — instead of streamlining roadways, the "three E's" were refashioned to calm roadways in the name of traffic safety. Each "E" complemented the others — calling on different capabilities from the public sector, on a range of time-frames, and from a range of budgetary pots — balancing like a three-legged stool.

Now in the 21st century, enforcement, education, and engineering each face fundamental questions calling into doubt their established professional practices and their overall efficacy. With each leg individually wobbling, the three-legged stool of the "three E's" may no longer work. A handful of planning consultants, public-sector officials, and academic researchers are thinking past the "three E's" to more effective strategies to manage traffic safety policies and projects across the US.

But before tossing out this this framework, let's give it a try. Enforcement, education, and engineering are useful lenses through which to view traffic safety along a few blocks of Santa Clara Ave. on the eastern side of Alameda Island. It's the site of that fatal crash in 2011, it's since been designated as a Tier 2 High Injury Corridor and a High Crash Intersection, and the city has just begun implementing what may be the first redesign of this roadway since that time.

Enforcement

These thoughts on enforcement are about Alameda in general. For more on Santa Clara Ave. in particular, skip ahead to the education and enforcement sections.

Drivers speeding on ahead. Drivers rolling through stop signs. Drivers rounding corners. Drivers ignoring pedestrians, ignoring cyclists, ignoring other drivers. When people see this kind of bad behavior — whether it be on this section of Santa Clara or on the wider streets of western Alameda or Bay Farm — the first tool some ask for is the "E" of enforcement. Get some police out there and hand out some tickets!

And yet with armed law enforcement personnel can come other consequences. What's the difference between police officers actively enforcing traffic safety by pulling over and ticketing drivers who exhibit bad driving behavior and police officers conducting "pretextual" stops that add up to patterns of racial bias? When do unnecessary stops by police lead to awful and unjust outcomes?

As a white person and an amateur in the field of transportation, I don't feel I know enough to tackle these questions — and I get the impression that many trained professionals in transportation are just as uneasy. Add to these challenges that Alameda has a fraught track record of policing (not to mention intersecting topics such as discrimination in housing).

But most of the potential alternatives to armed police for traffic safety enforcement have yet to materialize:

- How about using automated cameras to enforce speed limits and issue tickets? Not allowed under California law (although San Francisco, Oakland, and a handful of cities are hoping to gain the right to pilot speed safety cameras).

- Most new cars and SUVs have sat. nav. systems and advanced electronics... why can't they limit their drivers from going, say, 50MPH on a roadway with a 25MPH speed limit? Both the EU and the UK now require "intelligent speed assist" systems in new cars. But the US National Highway Transportation Safety Administration is just in the middle of rulemaking to potentially adopt speed limiters to prevent long-distance truckers from going, say, 90MPH on a 65MPH freeway. No one is holding their breath for the NHTSA to act on speed limiters for passenger cars.

Aside from principles and laws, there's also a practical question of whether enforcement is a viable approach to traffic safety in Alameda: Are there police officers assigned to traffic enforcement? My understanding is that since the Great Recession, Alameda has barely assigned any officers to traffic enforcement.

Alameda' Vision Zero Action Plan aims to balance these competing concerns by "focus[ing] enforcement on dangerous moving violations." That is, using whatever limited enforcement resources are available to target the driving behaviors actually associated with causing auto crashes (and de-prioritizing police interactions with the public where there is not a clear safety issue).

In sum, enforcement of traffic laws is still a component of traffic safety along Santa Clara Ave. and throughout Alameda — but with ethical questions about its tradeoffs and practical limitations of being a comparatively low priority for the police department.

Education

"In Bay Area, Youngsters Are More Prone to Bicycle Accidents" read the headline on July 2, 2011 in The New York Times. The article began with:

For the Sorensen family of Alameda, the sound of knuckles rapping on the garage door was a familiar annoyance. It was their 13-year-old son, Brandon, who knocked on the door so frequently to put away his bicycle that his parents finally got him an access code to open the garage on his own.

“Now, I would love to get up every couple of minutes to get him,” said his father, Kurt Sorensen, a Southwest Airlines employee.

Brandon was riding his bicycle through an Alameda intersection on a rainy Monday afternoon last month when he was struck by an S.U.V. By chance, his mother, Tammy, came upon him lying in the street as she drove past. She held her son one last time; he died at a nearby hospital.

A Bay Citizen analysis of bicycle accident data from the California Highway Patrol found that young cyclists like Brandon are at the highest risk. The analysis shows that in the Bay Area cyclists ages 10 to 19 were involved in more traffic collisions — more than 3,200 from 2005 to 2009 — than any other age group.

Nearly half of those accidents involved boys ages 12 to 16.

In a region filled with thousands of adult cyclists, including daredevils who barrel through congested cities at high speeds, data showing that youngsters are most prone to accidents surprised even bicycle advocates. They said it showed the need for early education about traffic laws and safety.

I share this long excerpt for two reasons: This is the crash I mentioned in the introduction — the crash that took place at the intersection of Santa Clara Ave. and Everett St. And yet this piece has little to say about that intersection as a place — or about that intersection as a factor in the crash itself — this piece is primarily about "the need for early education about traffic laws and safety."

As a parent of young children, I'm all too cognizant of our duty to teach our kids to be safe in the hard world. And yet, I will be blunt: the framing of this article sounds like it's blaming the victim. (Here's the full article — feel free to come to your own conclusions.)

I'm mainly just struck by how focused this article is on asking children to accommodate themselves to our awful adult world.

(Perhaps in their grief, some of the people mentioned in this article found comfort in education as a means to decrease the odds of this happening again. It's not my place to question that.)

I do question how the overall framing of this article on education as the means to keep middle-school-aged boys safe on bicycles leaves out of the frame so many other important factors.

If only young boys could learn to stop getting in front of cars! with no mention of the drivers of the cars, the size of the cars, the geometry of the roadway, the presence or lack of bike lanes, the design of bike lanes relative to auto lanes and crosswalks. (Nor a mention of the other "E" of enforcement to keep adults in cars attentive and less likely to lapse into unsafe driving around cyclists or pedestrians.)

That's one of the key problems with the "E" of education. It's comparatively easy. It's comparatively cheap. It feels positive and forward-looking. Therefore, it can draw commitment away from harder, more costly, more politically or bureaucratically contentious solutions.

Engineering

With all the downsides of enforcement and education, many traffic-safety advocates have focused their efforts on the "E" engineering: the concrete, paint, and signage of streets, roads, and highways.

Let's look at that these physical features of the Santa Clara/Everett intersection:

In engineering terms, the existing conditions are (in my layperson's description):

- a two-way intersection without a traffic signal for motorists

- a four-leg intersection with marked crosswalks (with "zebra" markings for two of the legs) for pedestrians

- two-way stop, with no control for thru auto traffic on Santa Clara Ave.

- the intersection itself is not orthogonal; the cross-section of the street is wider on the left (northwest) side and reduces to a narrower width on the right (southeast side)

For motorists, this is, in effect, a physically inconsequential intersection midway between the signalized intersections at Park St/Santa Clara and Broadway/Santa Clara — an intersection to get through in order to reach the next light.

For pedestrians, this is, in effect, an intersection to stand and wait at — to wait for all the cars to clear before attempting to cross. Even for motorists with stop signs, the stop "bar" line is so far back from the roadway that they will likely drive into the crosswalk to get a better view of passing traffic, meaning that pedestrians have to wait at the "controlled" crossings across Everett as well as the uncontrolled crossings across Santa Clara.

For cyclists, this is just an intersection to be confused by. Do you take it like a car? Do you take it like a pedestrian? The physical design leaves multiple options but no clearly recommended or protected option.

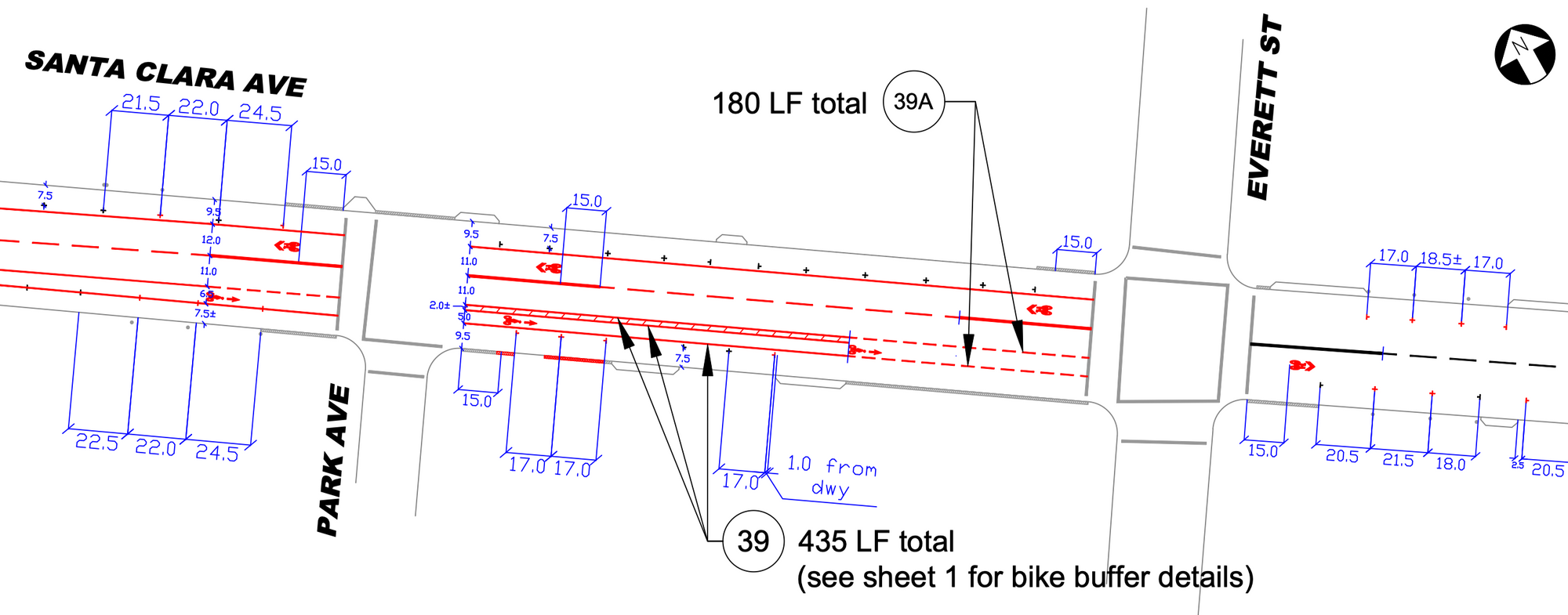

The project that has just begun is changing the striping at the intersection to look like this (thanks to city staff for sharing engineering drawings):

Cyclists will have a bike lane when they are going eastbound along Santa Clara (to the right in the above drawing) until they reach Everett, where they will have to merge into the auto lane. Cyclists going westbound along Santa Clara (to the left) will have "sharrows" along Santa Clara until they reach Park St.

Per a letter from Public Works to local businesses announcing the current re-striping project:

This project will refresh faded gray, red, and yellow curbs in these areas.

Additionally, the intersection of Santa Clara Ave/Park Ave will be daylighted per our current standards.

Parking T’s will be refreshed, and some will be adjusted to improve parking maneuvers or improve access into or out of adjacent driveways.

Bike routes and lanes will be installed where they fit and where they can be added based on current traffic design [principles].

— City of Alameda Public Works, September 20, 2023

What's changing — and what is not changing — on Santa Clara Ave. is perhaps a representative example of current traffic design principles and the "E" of engineering.

The good news is that the City of Alameda, like other forward-thinking cities, is "daylighting" as many intersections as possible. By placing red "no parking" zones near intersections, engineers improve visibility for passing drivers to better see pedestrians approaching crosswalks and for turning drivers to better see oncoming auto traffic. Alameda policy empowers staff to decide how to daylight intersections, with no involvement of elected officials. Daylighting will be an improvement to the nearby intersection of Santa Clara and Park Ave.

The mixed news is that bike lanes are included to this project as a convenience, not as a necessity. Existing bike lanes will extend further along Santa Clara Ave than they have before — that's nice! — but the lanes will end without ceremony at Santa Clara and Everett. The intersection looks, at least on my read of my read of these plans, as if it will be just as awkward for cyclists after the changes as it was before the changes.

Could this engineering project do more to improve the safety of this intersection for cyclists and pedestrians? Yes, it could — in theory. NACTO's candy-colored handbooks have many vivid illustrations of engineering designs that could be beneficial to the Santa Clara/Everett intersection. But in practice? It would take time and effort to do the type of study that's required to consider imposing turn restrictions or adding traffic controls (like more stop signs). Working within the geometric constraints of the intersection would be a challenge for all designs; to create bulb-outs for pedestrians might require closing a side of Everett to through auto traffic, while continuing a bike lane along Santa Clara would require removing some on-street parking spots. Physically raising the height of the intersection would be a useful signal to drivers to slow down and proceed with caution, but this could also involve rebuilding curbs and drainage. The city is under-resourced and under-staffed for its current load of roadway maintenance projects and safety improvement projects as it is. It's probably not practical to ask each and every street infrastructure project in Alameda to be the best it can be.

So, this is the state of the "E" of engineering. It's the most effective of all three approaches the traffic safety. The relevant professions have been updating and adapting their guidelines to deliver "complete streets." There's money, albeit never enough, to deliver some maintenance and improvement projects over time. As of this year, Alameda city departments are now working together to run the Rapid Response after Fatal Crashes Program, which is systematically building out infrastructure improvements to the sites of this year's two fatal crashes to date.

And yet engineering can't bear the full weight of traffic safety alone. It's not moving quickly enough to adapt as a profession or quickly enough in terms of delivering projects on the ground. It can't make up for the major increases in vehicle horsepower and hood height or the major decreases of our care and concern during the Trump administration and the pandemic. Maybe that's just too much to ask of one field.

New frameworks for traffic safety

What now?

The consulting firm that drafted the City of Alameda's Vision Zero and Active Transportation plans proposes the "new E's" of ethics, equity, and empathy.

Those are all nice words. Can't disagree with 'em. (To be honest, perhaps thinking through these topics and writing these blog posts is my own attempt to practice some of those values.) But what specific direction do these words provide to elected officials and to on-the-ground staff tasked with improving traffic safety?

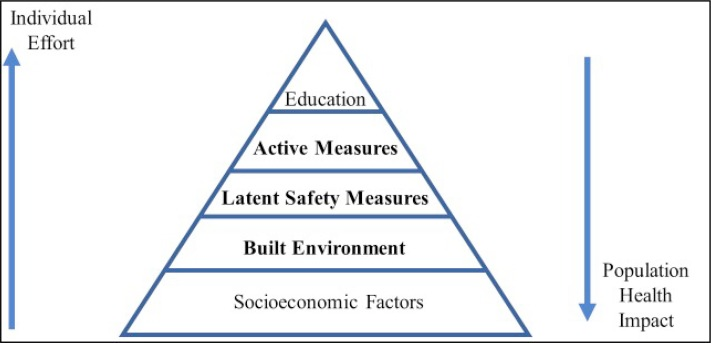

At the tail end of August's Transportation Commission meeting, I used the "commission communication" item on the agenda to briefly describe a recent academic paper titled The Safe Systems Pyramid: A new framework for traffic safety. (Since it was determined that a PowerPoint slide with a picture couldn't be presented without being noticed in advance under the Brown Act, I instead used my fingers to attempt to draw out the diagram that follows :)

In place of the "three E's," the authors from Georgia Tech, University of Minnesota, and UC Davis propose a model for traffic safety based on well-established public-health frameworks:

At the top, education calls on much individual effort, with comparatively little impact on the health of the overall population. Next, active measures like seat belts, helmets, safety-related signage, or enforcement by an officer. Latent safety measures are less noticed but have a wider impact — for example, speed limiters in cars, signal timing to encourage slower traffic, or automated speed enforcement. Built environment includes the physical design of streets and their surroundings. Finally, socioeconomic factors includes the context around these streets — for example, land-use and housing policies that enable (or do not enable) people to live near where they work or live within a short trip to their daily necessities.

In place of the "three E's," the Safe Systems Pyramid offers more options. It encourages the layering of multiple interventions. It also acknowledges that not all interventions will have an equally sized effect. Education is still part of the framework, but it is not given co-equal weight like in the "three E"s framework. Enforcement is one of many possible active measures. Engineering can happen in multiple ways — some that are more explicit and visible to roadway users, and others that change the underlying geometry and flow of an entire street.

The Safe Systems Pyramid can't make it any easier to make the hard decisions required of many interventions at lower/more impactful levels. But it may give us more ways to see everything that's gone wrong when a tragedy occurs on a street here in Alameda. And it may give cities, states, and funders and regulators at the federal level a more strategic means of pursuing traffic safety through multiple parallel interventions.

That said, there is some value in some of the components and sensor systems that are being created for autonomous vehicles. Some new cars are now equipped with cameras to detect pedestrians and stopped vehicles in a roadway. Applying emergency braking in this situation is not always going to work, but it can provide another "layer" of protection.

Instead of trying to remove steering wheels from cars, it would be more useful to add these types of sensor systems, along with speed limiters, and breathalyzers.

We certainly can't enforce or educate our way out of awful accidental deaths on our streets. I wish we could engineer these problems away — but there likely isn't enough time, money, concrete, and flex-posts for that strategy to succeed alone. Instead, it's in the layering of multiple interventions where hopefully we can make some positive difference: from teaching our kids to cycle carefully, to teaching ourselves to drive our much larger vehicles with even more care, to advocating for automated speed enforcement, to looking at even the mundane maintenance of our streets and asking how we can do better. Because, to be frank, thinking of kids dying on American roadways at low-but-non-zero odds — the cost of doing business for our way of life — is a heartbreaking.