This past week I was originally planning to head down to Los Angeles for a small conference in my niche of work. I've been going to this series of workshops for ~10 years, typically rotating between SF, NYC, and DC. But with headlines of international visitors and even lawful permanent residents detained and mistreated by federal authorities at American airports, a number of the long-term participants from other countries didn't feel comfortable entering the United States. So instead, the conference was relocated to a kinder and more law-bound country, and I flew up to Vancouver for a couple days.

Vancouver and the Bay Area have much in common:

- an economic arc from native populations with subsistence practices, to resource-extraction from broad hinterlands, to knowledge workers practicing design thinking to bring digital delight to user personas

- a Pacific orientation, with long-term migration and ongoing cultural and culinary connections with East Asia

- metro regions surrounded by mountains and cut by water, with formerly industrial ports transformed into promenades and parks

- international flows of capital and investment

- local uniforms of pants designed for yoga and jackets designed for ice climbing, worn in offices and supermarkets

The two places have so much in common that often movies ostensibly set in San Francisco are filmed in Vancouver. (At the conference, I joked with local transit agency staffers about how their blue and/or green Translink buses stand out in the background of many movie scenes that should feature SFMTA's current silver and red or classic orange and white.)

And yet there are also key differences between the two regions that the Bay Area — and Alameda in particular — can learn from:

- build up, near transit

- run trains and buses as frequently as possible

- protect cyclists and walkers with concrete, rather than paint and plastic

(There are also key differences in the national immigration policies that apply to Vancouver and the Bay Area — and have affected regional real-estate values in different ways — but that's beyond this blog's scope.)

Build up, near transit

"Vancouverism," in the words of Wikipedia, is:

characterized by a large residential population living in the city centre in mixed-use developments, typically narrow, high-rise residential towers atop a wide, medium-height commercial base, significant reliance on mass public transit, creation and maintenance of green park spaces, and preserving view corridors

As the city's SkyTrain has extended across the region, Vancouver and neighboring cities have proactively planned for increased residential capacity around transit stations. As the arrival of speedy transit lifts land values around stations, public agencies use a taxation technique called land-value capture. Landowners are required to pay "community amenity contributions," which represent some of their increased property values being paid back into public coffers.

It's a virtuous cycle of sorts, balancing both private investment and public services. And the region's expanding population is directed toward existing urban areas, near transit stations, rather than spread out into wild lands.

Run trains and buses as frequently as possible

Vancouver's Translink is one of the best performing transit agencies in North America. In part it's due to the region's efforts to place housing near transit. In part it's due to the transit agency's efforts to run frequent transit. This combo makes transit a convenient option throughout the day, for a wide variety of trips.

This isn't just transit for when a knowledge worker wears their yoga paints and technical jacket to the office; it's also a transit system that supports elderly people going to doctors appointments, families going on outings, and college students traveling on the highest ridership bus line in North America to the University of British Columbia.

SkyTrain, the rail system, is fully automated (and fully grade separated). It's just like a people mover at an American airport or a Disney resort — across the entire region. The trains are short (only 2 cars, compared to a BART train that can be up to 10 cars) but make up for their relatively small capacity with their frequency. When one train was too crowded in the evening, my colleague and I waited for the next — which arrived in approximately 90 seconds.

When recently asked in Bloomberg News "Are there particular lessons from TransLink’s experience that might be useful to transit staff and advocates in other North American cities?" the CEO of Vancouver's transit agency replied that:

I would emphasize frequency. Running the bus every 30 minutes isn’t going to cut it if you want to grow ridership. With 30-minute service, if one bus doesn’t show up it’s now 60-minute service. Folks aren’t going to rely on that.

In Vancouver, we have lots of buses run with headways of five minutes or less. The SkyTrain is running every three or four minutes, and because it’s driverless, we have the capacity to run even more. That was extremely helpful when Taylor Swift completed her Eras Tour here last year, and we were able to empty out a 55,000-person stadium in 45 minutes because the SkyTrain came every 90 seconds.

Personally, I take the bus every day, and it runs every 10 to 15 minutes. I live my life without a transit schedule, and I like it. I think that’s how most metro Vancouverites live their lives, too.

Protect cyclists and walkers with concrete, rather than paint and plastic

In the central business district where I stayed and in the neighborhoods I explored around train stations, I found many low wall concrete barriers. Instead of trying to calm vehicular traffic with "quick build" installations of paint or plastic, the traffic engineers of Vancouver deploy concrete.

In contrast with K-rails that are a common feature along American freeways (and were apparently first invented in California), low wall concrete barriers are designed for urban contexts. They're lower (obviously) and they have less obvious design features like drainage channels underneath.

In contrast with the advisory message of paint, these low wall concrete barriers physically stop drivers from swerving into this cycletrack:

Vancouver planners also deploy low wall concrete barriers to serve as modal filters, allowing through certain modes of traffic and blocking others:

And in a striking contrast with Alameda's flimsy plastic A-frame barricades at the entries to our slow streets, Vancouver engineers arrange low wall concrete barriers to mark the entries to their "neighbourhood slow zones":

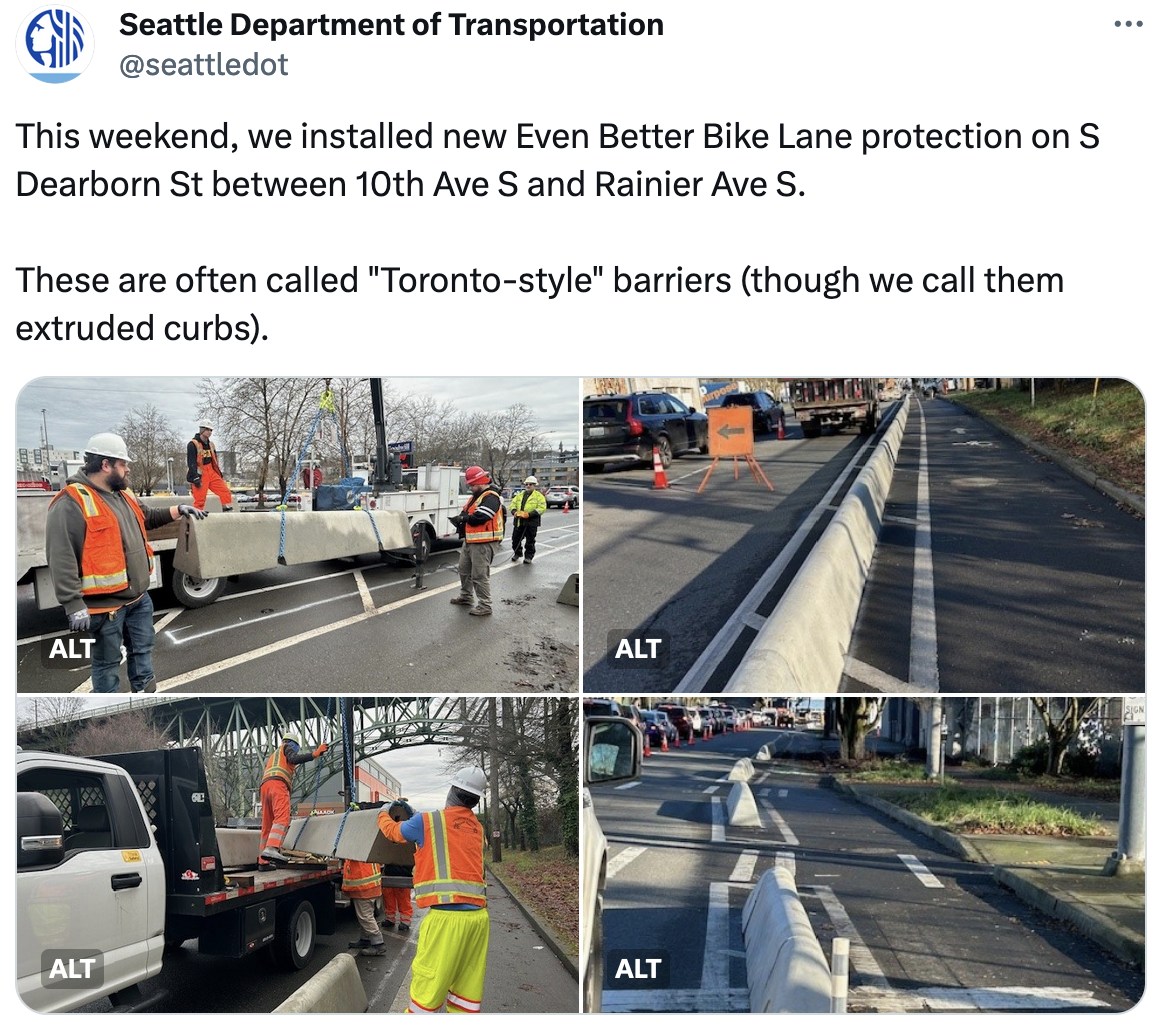

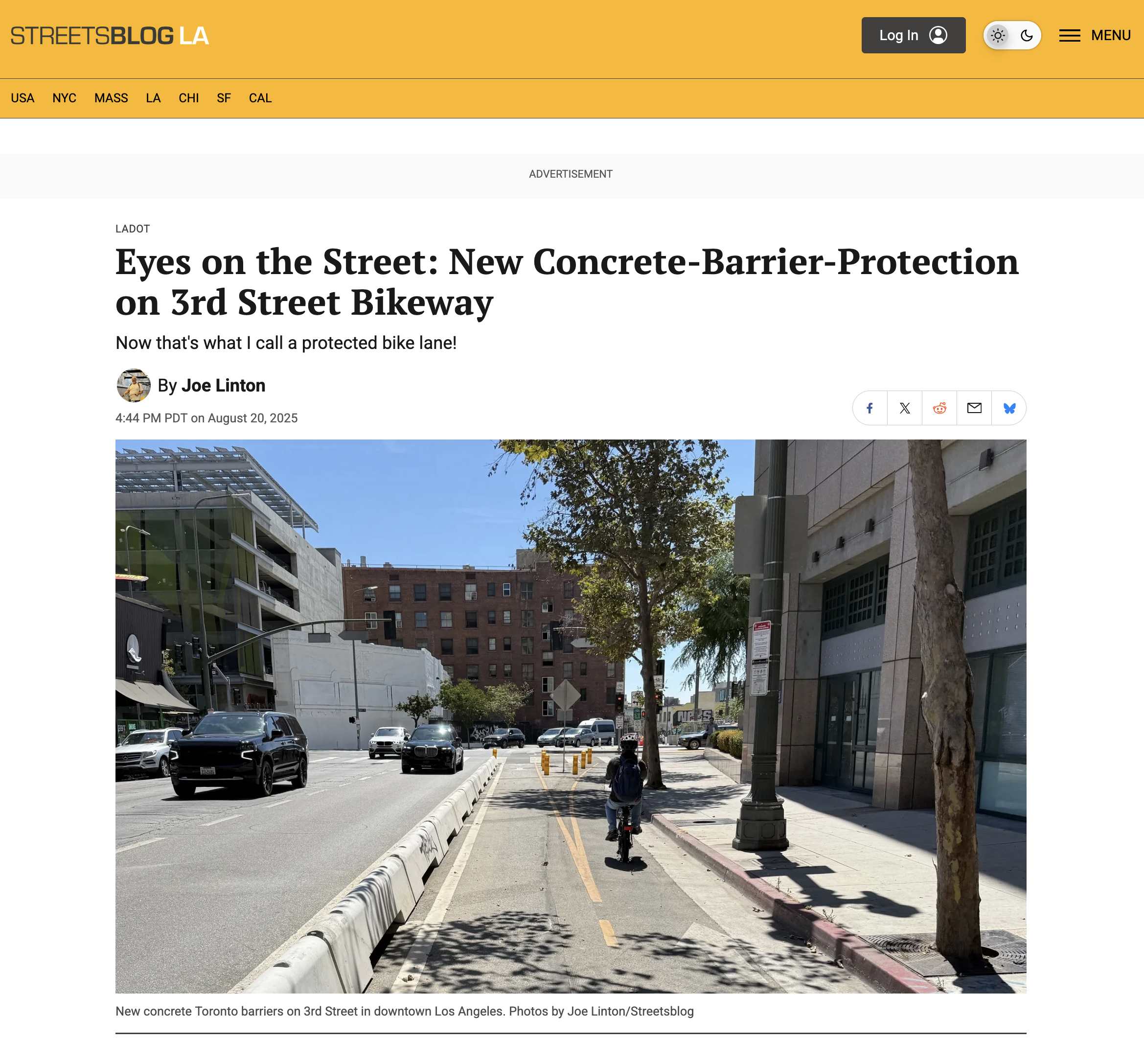

Seattle and Los Angeles have recently started deploying low wall concrete barriers to protect bike lanes and cycle tracks:

Left screenshot from the Seattle Bike Blog and right from Streetsblog LA

Alameda would also do well to learn from Canada and add the "Toronto barricade" to our own local street-improvement toolkit.

Thank you to my hosts in Vancouver for a warm welcome and a pleasant visit. I hope our own country will once again reciprocate Canada's neighborliness in the future.