"Steph and Ayesha Curry oppose upzoning of Atherton property near their home" is the headline in one of the small newspapers on the mid-Peninsula. The fact that yet another big name with progressive politics is NIMBY when it comes to their hometown isn't news. But the final paragraph of the article is interesting news:

The plan is due to the state Housing and Community Development Department (HCD) on Tuesday, Jan. 31, and the Atherton City Council will vote on the final version of the plan at a Jan. 31 meeting at 2 p.m.

— The Almanac, January 27, 2023

"The plan" is Atherton's Housing Element, which is supposed to cover how the town will accommodate housing for more people of more income levels between 2023 and 2031. This eight year period is the "sixth cycle" of California's housing allocation process. This overall process has been happening for decades. So why is the Town of Atherton leaving adoption of its plan to the very day of the deadline? With the councilmembers starting their meeting at 2 p.m., will they be able to listen to public comment, debate, and adopt a Housing Element by the due date, 10 hours later?

Of the 100+ municipalities and counties in the Bay Area, Alameda was the very first to adopt a Housing Element for the sixth cycle. (Alameda City Council voted 3-2 to adopt its Housing Element on November 15, 2022.) If our experience is any measure, Atherton will not pull it off in time.

All of this is already well known to California and Bay Area housing advocates. Still, I figure it's a useful story to retell as a unique political success for Alameda.

Carrots and sticks — but no solutions

Over the last six years, the state legislature and two governors have addressed the state's housing crisis with a range of new "carrots" and "sticks" to encourage and cajole the development of new housing by cities, towns, and counties throughout California.

One of the most consequential of the "sticks" turns out to be Senate Bill 828. In past cycles of the state's housing allocation process, the California Department of Housing and Community Development would give target numbers to each region; then each regional planning body would divide those into target numbers for each of their cities, towns, and counties. But neither the regional planning bodies nor the state would hold any place to account for not meeting their targeted. Cities, towns, and counties could propose the same sites for new housing every eight years, and even if no housing ever appeared — perhaps due the those sites being bogus or having overly stringent zoning — no one would call their bluff. SB 828, proposed by State Senator Scott Wiener and signed into law by Governor Jerry Brown in 2018, added sticks to this process.

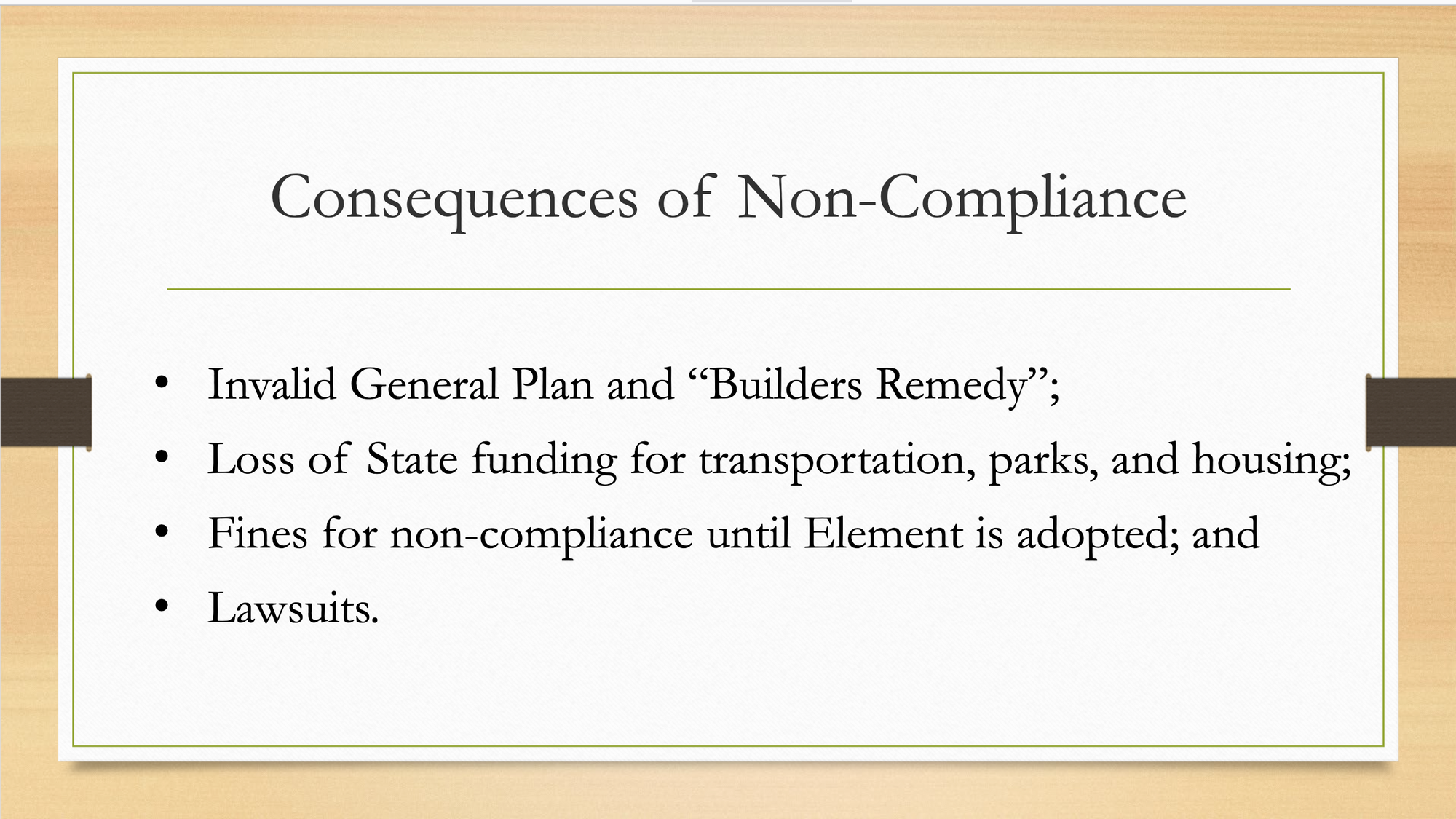

It's because of SB 828 that the sixth cycle of the RHNA process (as this state housing allocation process is known) is of substantially more importance than in past decades. This time there actually are consequences if Alameda, Atherton, and other places fail to each adopt a Housing Element that is judged as "compliant" by the state:

Despite adopting the sticks of requirements and carrots of incentives for localities, the State of California has shied away from passing actual direct solutions. SB 828 was a sneaker wave of a bill in part because most of the attention at the time was directed at one of Senator Wiener's other housing bills. The bill first known as SB 827 and then known as SB 50 earned headlines in national newspapers, spittle-inflected rants from opponents, and enough opposition within the state legislature that it never passed. These bills would have allowed denser housing near public transit throughout the state, overriding local zoning codes. Those who prize "local control" cried a storm about how the state could not and should not oppose "one size fits all" solutions. Opponents succeeded in that they prevented SB 827/SB 50 from passing. Opponents failed in that they've made the jobs of every city councilmember and county supervisor in the state a lot harder, perhaps to the point of being impossible.

Localism is determinism

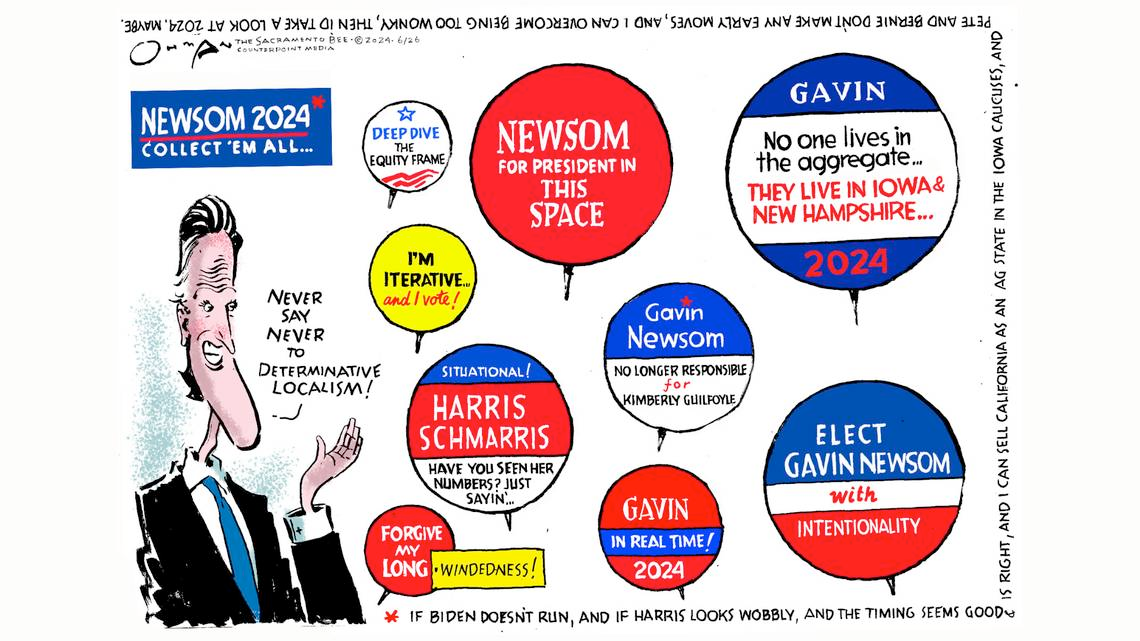

When Governor Gavin Newsom doesn't want to make a hard decision that will likely earn him more scorn than plaudits, he turns to one of his go-to phrases: "localism is determinism."

When this strategy is implemented well, each county/city/town/school district/etc implements broad state mandates and refines its own specific solution to the given problem — a solution that best fits the constraints, capabilities, and preferences of each place.

When done poorly, it's a way to pass a "hot potato" from Sacramento down someone else at the local level to handle — and to receive the blame.

In the case of housing, it's been the state legislature (rather than the governor's office) that equivocates and passes the potato.

One of the reasons why some legislators are so fearful of taking any zoning controls from locals and offending local NIMBYs in the process: Those legislators are likely to again run for city councils and county boards of supervisors. There are many pernicious side effects of strict term limits in the California state legislature — and this is one of them. After rising through the ranks to get to Sacramento, many senior leaders return again to the cities or counties where they originally made their name. Even though they have been elected to decide on state-wide issues, their political compass is still finely tuned to their grumpy neighbor who may be ready to vote against them on a future city-level ballot.

(Here's an example of a "downwardly mobile" state legislator: Scroll back up to that photo of Jerry Brown signing legislation in 2017. To his right is Kevin de León, who at the time of the photo was the leader of the California State Senate. He got termed out of Sacramento and now he back in Los Angeles as a city councilmember — at least for the time being.)

Passing the hot potato

The state-wide mandates of SB 828 without the state-wide solutions like SB 827/SB 50 is the worst combination for many local leaders. City councils and county boards of supervisors are now being held accountable for adopting compliant Housing Elements. If they aren't able to put together policies, zoning code amendments, and programs, then its their fault. If they can't get a majority to vote to adopt a plan and send it to Sacramento for review, then its their fault. If they succeed at a compliant Housing Element, they may then have to face enough angry local voters that they'll lose their next election.

It was an open secret that some local elected leaders actually wanted a state-wide solution like SB 827/SB 50 to pass. Then they could be ranting loudly about zoning code changes that are all "Sacramento's fault" and "take away our local control" — at the same time as they are quietly pleased for no longer being responsible for leading local debates about how and where to accommodate new housing.

Some members of the Atherton City Council probably wish they could be relaxing and just complaining about the state at this point — rather than needing to finalize the hard choices that go into a Housing Element by the end of January 31.

Alameda passed the test

Was that a wise move to let each locality fine-tune its own solutions to provide more housing? Or was that the passing of the buck by state-level leaders hesitant to burn their own political capital to pass state-wide solutions?

Here in Alameda we can now say the answer to both questions is "yes."

The adopted Housing Element and Zoning Amendments are almost certainly a more refined set of zoning changes and housing programs for Alameda than a "one size fits all" state-wide rezoning law. And also, the City Council and volunteer Planning Board members and city planning staff have had to handle so many strong and divergent opinions, not to mention rudeness and misinformation, over two years. It's been a political stress test of all the local civic institutions.

A partial list of ways that Alameda passed the test:

- Responsible electeds: A slight majority of electeds on City Council doing the responsible thing. Throughout the nearly two years of the Housing Element process, Mayor Ezzy Ashcraft, Vice Mayor Vella, and Councilmember Knox White oversaw the process without interfering in the work being performed by city staff, consultants, and the Planning Board.

- Empowered staff: Andrew Thomas, the city's director of Planning, Building, and Transportation, has been working in Alameda for roughly 20 years. Watching him hold forth at public meeting after public meeting on the Housing Element, I could see how Alameda is both fortunate to have his expertise and to have someone on staff who's accrued enough influence to be able speak frankly to electeds and prominent members of the public. His staff and consulting team seemed similarly empowered to do the work that was being asked of them — preparing a compliant Housing Element and drafting amendments to the existing zoning code, for adoption by the electeds.

- Side note about consultants: Some housing activists who follow Housing Element throughout California are suspicious about Placeworks Inc. The firm is providing consulting services to dozens and dozens of cities on their Housing Elements. Some of those Housing Elements have some bogus sites identified for new housing and some questionable programs and policies — the type of stuff that shouldn't happen under SB 828. Is Placeworks leading a conspiracy to create bum Housing Elements? I have no idea. But looking at Alameda's success with a compliant Housing Element, I think we can say that it's really the electeds and the staff that matter. The consultants are there to implement the goals of the electeds as articulated and refined by the staff. If a city's electeds and staff are making a good faith effort to meet the state's "sticks" and to earn the "carrots," then Placeworks can support them in meeting those goals.

- Residents and business owners worried about housing scarcity, costs, and homelessness: It's a small set of people who attend and speak at synchronous City Council and Planning Board meetings. I can now recognize the names and voices of the handful of "usual suspects" — and I have perhaps become one myself. But this small group isn't representative. By spreading the Housing Element process over two years, Alameda's electeds and staff were able to engage many more stakeholders, collect input on multiple drafts, and do more than just "straw polls" of the handful of people inspired or incensed enough to show up on Zoom at 7 p.m. on a Tuesday evening:

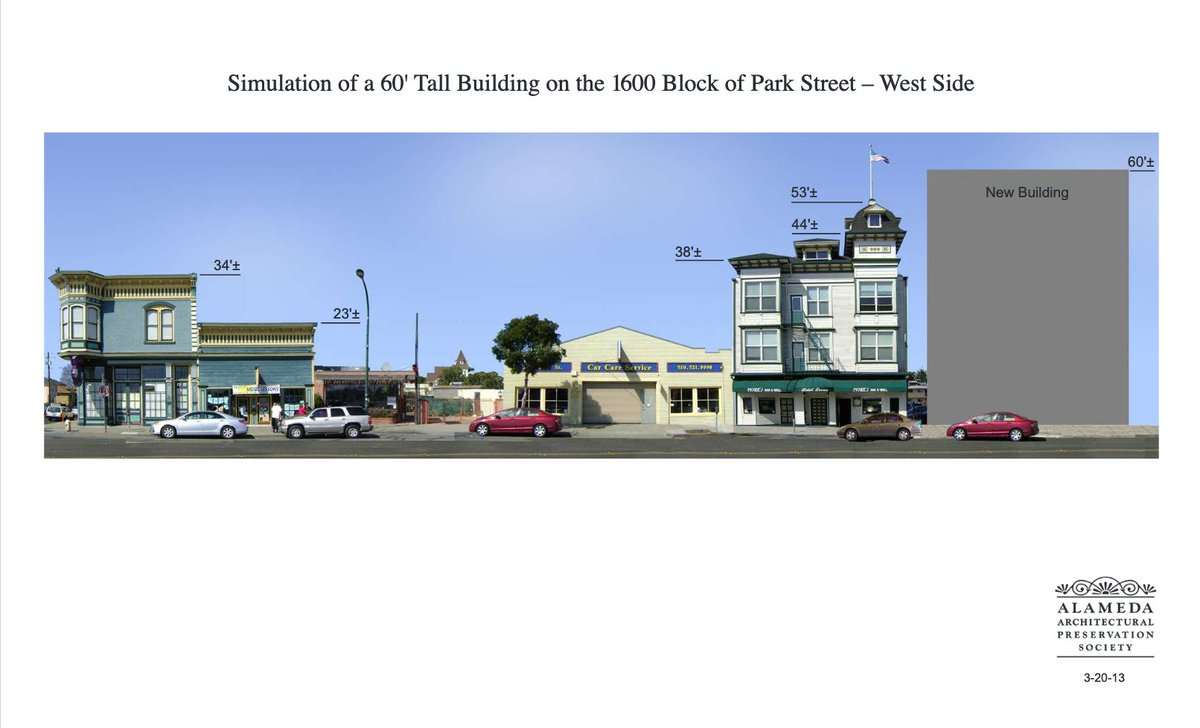

- Opposition: Some of Alameda's success at passing a compliant Housing Element may also be attributed to the local opposition. In the "hot house" of a public comment period, loud arguments against the Housing Element sounded powerful: Protect our shopping centers! Save our neighborhoods! Traffic! New housing is unaffordable! Emergency evacuation of the island! Emergency evacuation — with armed guards to ensure we're all able to safely traverse Oakland after we evacuate the island! (I wish I were making up that last summary of an actual public comment.) Groups like the Alameda Citizens Task Force (ACT) and the Alameda Architectural Preservation Society (AAPS) were unrelenting in their opposition to the Housing Element process — but over the two-year period, there was little coherence to their arguments in opposition. For example, for a few weeks, ACT tried to threaten the city and the state over the definition of the word "it" in a portion of the state government code — but that nitpicking attempt to halt the Housing Element process didn't work, and ACT just switched to another, different set of arguments. The anti-arguments never cohered into a single strategy. It was always just spaghetti flung against the wall to see what might stick. (Last I read, ACT was fundraising to launch a lawsuit against the City of Alameda, so never say never.) Similarly, AAPS argued again and again to reduce heights, densities, unit counts — any parameter that could be reduced in the zoning code to reduce the number of new people who might be able to live in Alameda, they wanted to reduce it. And yet instead of trying to articulate a compelling vision, AAPS just fell back repeatedly to the Panglossian shtick that Alameda is the best of all worlds in its exact current form:

- Supportive voters: Alameda's elected leaders who supported the Housing Element process didn't do so just because it was the right thing to do — they also supported the process because they were representing a majority of their constituents. These are the same constituents who have voted State Senator Nancy Skinner into office repeatedly. (Skinner represents Alameda and the rest of the inner East Bay in the State Senate — and deserves just as much credit as Scott Wiener for her pro-housing legislation.) And these are the same constituents who report housing and homelessness as at or near the top of their list for the most pressing public problems. Alameda voters were sufficiently pleased with the Housing Element in its substance and in the way it was developed over two years to re-elect Marilyn Ezzy Ashcraft as mayor. Her sizable lead over her NIMBY challenger demonstrated how many voters in Alameda are pro-housing when they trust the process and the messenger.

Here's the thing: Alameda was fortunate to have a majority of elected officials who were responsible, who enabled staff and consultants to do the hard detailed work, and who helped guide voters and other stakeholders through the two-year long process of adjustment. It was so successful of a process that it let deniers and freeloaders ride in the wake: Councilmember Tony Daysog, who voted against the Housing Element, ran for re-election based on the successful track record of the City Council and this year he's Vice Mayor Daysog.

There's more work to do to address the housing crisis in Alameda, but the city did pass the political stress test of adopting an SB 828-compliant Housing Element successfully.

Beating the buzzer

Back to the original question of this post: Can Atherton pull it off at the last minute and adopt a compliant Housing Element tomorrow?

To succeed, I think they'll need a similar mix of enough electeds who want to do the right thing, staff who aren't afraid to give unvarnished advice to the electeds, enough local stakeholders who appreciate making a good-faith effort, and enough time to have work through details.

That last item probably can't be overstated: time. Alameda took almost two years to prepare this Housing Element and the associated zoning amendments. (While the state doesn't require zoning changes immediately when the Housing Element is submitted, Alameda made an especially good-faith effort by having City Council adopt both at the same time.) Time was needed to work through so many details and prepare hundred of pages of plans and zoning code changes. Time was also needed to have repeat conversations. The most dedicated NIMBYs were just going to keep on NIMBYing until the final vote — but many other stakeholders had valid concerns, worries, comments, and suggestions that took time to address. Some concerns may have even just been addressed by familiarity — the familiarity of seeing a process run over the course of two years.

I don't follow local politics in Atherton, so I don't know how well it's doing in these different respects. Do they have the electeds, the staff, and the time to submit a compliant Housing Element? You might also ask whether they even want to have a compliant Housing Element in Atherton. I don't know. (One housing advocate predicts that Atherton along with most other Bay Area cities will fail and will receive the "builder's remedy," which means losing all local control of zoning and permitting.)

What I would predict with confidence: Some members of the Atherton City Council will be in their meeting tomorrow night, wishing that the legislators in Sacramento had passed a state-wide zoning bill like SB8 27/SB 50 years ago, wishing they could sit back in their chairs, wishing they could be shouting about how awful it is to lose local control! — while also silently breathing a sigh of relief because the politicians in Sacramento had already taken the heat and made the hard decisions on their behalf.